Why Now is the Time to Look at Legionnaires’ Disease

Category: Mep

Written By: Jason Robison, PE

Date: October 4, 2021

Jason Robinson, PE, serves as one of Parkhill’s mechanical design engineers. He has experience in design multiple system types including hydronic (chilled/heating) water systems, packaged units, split systems, VRF, and VAV systems.

Jason Robinson, PE, serves as one of Parkhill’s mechanical design engineers. He has experience in design multiple system types including hydronic (chilled/heating) water systems, packaged units, split systems, VRF, and VAV systems.

Due to the pandemic and quarantining over the past year, many buildings and businesses closed for extended periods of time. As businesses reopen, it is crucial that building owners and facility managers understand the maintenance needs of these facilities that could affect the health of employees. One example is Legionnaires' Disease. There is an increased risk for an outbreak of this disease due to the water and air conditioning systems sitting with potentially no usage for weeks or months.

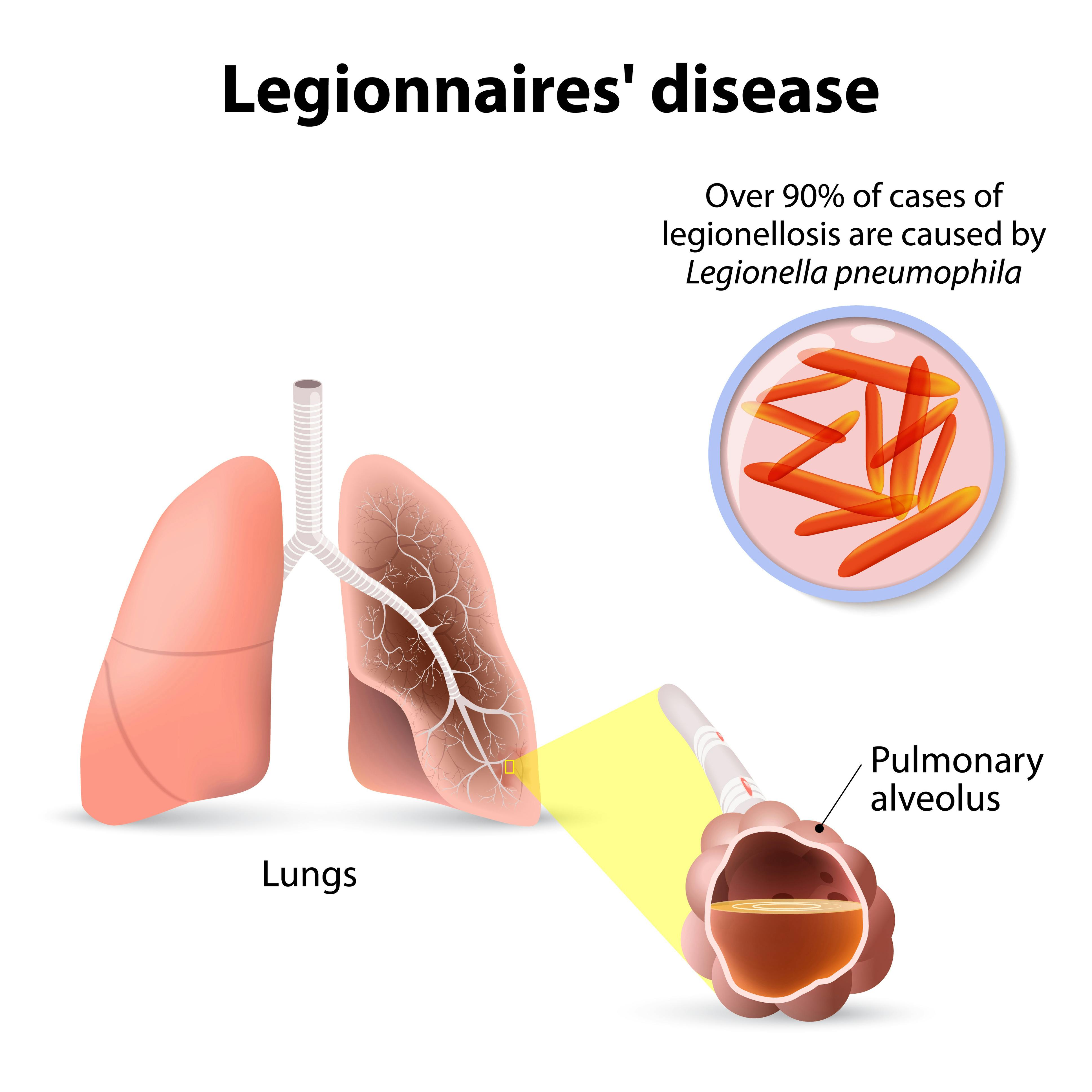

Just over 45 years ago, in the summer of 1976, Philadelphia hosted a large gathering to celebrate America’s Bicentennial. Hundreds of veterans associated with the American Legion gathered and stayed at the Bellevue Stratford for the conference. Within days, hundreds of attendees started reporting symptoms of pneumonia as well as headache, fever, and gastrointestinal issues. More than 200 people were infected at the conference; more than 30 died. With the considerable number of people infected at the same time at such a high-profile event, the CDC launched what was, at the time, its largest field investigation. In January 1977, after almost six months of investigations, Dr. Joseph McDade discovered the outbreak was caused by an unknown rod-shaped bacterium found in the lungs. Since the outbreak had been among members of the American Legion, scientists named the new bacterium Legionella, and the disease it caused was called Legionnaires’ disease.

While reviewing old cases after the discovery of the Legionella bacteria, the CDC linked the bacteria to a previous outbreak in 1968 in Pontiac, Mich. Those affected at the time had much milder symptoms, reporting only fever, chills, and muscle aches. These cases showed no infections in the lungs, so it was named Pontiac fever.

Legionella bacterium is naturally occurring in freshwater and soil, so it has been around for far longer than when it was discovered in 1977. Where Legionella naturally occurs, it is normally in exceptionally low amounts which generally do not lead to infection. Legionnaires’ disease is usually contracted from inhaling water droplets with high concentrations of the bacteria. Legionella bacteria can thrive and multiply in man-made systems, such as hot tubs, cooling towers, water heaters, fountains, swimming pools, and drinking water. Legionnaires’ disease cannot be contracted from drinking water with the bacteria unless you aspirate the water, in which case the bacteria could enter your lungs and lead to an infection. Legionella can also be inhaled when working with soil that has elevated levels of Legionella, but this is uncommon. Legionnaires’ disease cannot be spread from person to person, and new cases generally come from an outbreak in which people were exposed to the same source.

Legionnaires’ disease can emerge any time within two to 10 days after exposure to Legionella bacteria. Not everyone exposed to the bacteria will be infected. Risk factors that increase the chance of infection include smoking, having a weakened immune system, being 50 years or older, and having a chronic lung disease. Legionnaires’ disease is considered a severe form of pneumonia. The most common symptoms start with a headache and fever and then lead to a cough, chest pain, and gastrointestinal issues within a few days. The mild version of Legionnaires’ disease – Pontiac fever — commonly only results in headaches, fever, and muscle aches and will typically resolve within two to five days with no treatment required. Legionnaires’ disease can last longer but can be treated with antibiotics to help resolve symptoms. Those who have been exposed to Legionella should see their doctor as Legionnaires’ disease can be fatal. Currently, no vaccine exists for the disease.

While Legionella bacteria is naturally occurring, contracting the disease is quite rare. The number of cases of Legionnaires’ disease reported was just over 1,000 cases in 2000. It has increased every year since then, with the most recent data from 2018 seeing just under 10,000 cases of Legionnaires’ disease confirmed. Part of the growth of reported cases is expected to be from increased awareness. The number of unconfirmed cases could be much higher than reported since the symptoms are similar to pneumonia and the flu, and people can recover without treatment. Since the disease is not transmitted from person to person, the number of cases each year can vary, depending on the number of outbreaks and the size of each outbreak.

While Legionella can grow in various systems that contain water, most cases come from cooling towers and domestic hot-water systems. A cooling tower is an outdoor heat exchanger that utilizes air being blown upward with large fans to cool water falling through the airstream to a basin to be recirculated to the building. A standard design temperature to provide water to a building with a cooling tower is between 83 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit. While Legionella’s ideal growth range is around 90 to 108 F, Legionella starts growing at 77 F. This temperature, combined with the water drift, results in tiny droplets of water vapor being pulled and blown out of the fan into the air with the potential to spread Legionella to surrounding areas.

While Legionella can grow in various systems that contain water, most cases come from cooling towers and domestic hot-water systems. A cooling tower is an outdoor heat exchanger that utilizes air being blown upward with large fans to cool water falling through the airstream to a basin to be recirculated to the building. A standard design temperature to provide water to a building with a cooling tower is between 83 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit. While Legionella’s ideal growth range is around 90 to 108 F, Legionella starts growing at 77 F. This temperature, combined with the water drift, results in tiny droplets of water vapor being pulled and blown out of the fan into the air with the potential to spread Legionella to surrounding areas.

Similarly, hot-water heaters can provide a breeding ground for Legionella if not kept at proper temperatures. At a minimum, at a temperature of 120 °F, Legionella will survive but not multiply. Setting a water heater in the range of 122°F-139°F will kill 90% of the Legionella within one to two hours. Setting the discharge temperature at 140°F or higher will kill 90% of Legionella in two minutes. Also, moving water and avoiding stagnation will prevent Legionella from growing. Commercial hot-water systems are required to have a recirculation pump to continually circulate hot water throughout so that hot water arrives at fixtures sooner. The other benefit of this is that recirculation prevents water from sitting or cooling down to the bacteria’s ideal growth range temperatures in pipes.

Preventing Legionella growth can be as simple as maintaining movement and high temperatures in hot water systems. All domestic cold and hot water systems should have cleaning and disinfection done when installed. Systems like cooling towers that can operate in the bacteria’s growth range should have the water quality monitored and tested periodically for any Legionella in the water. These systems should also have chemicals that can kill Legionella added on a schedule to avoid any growth in the system. Some companies specialize in the treatment and prevention of Legionella to avoid large outbreaks.

While Legionnaires’ disease is uncommon and is far better understood than it was 45 years ago, spreading awareness of how to prevent outbreaks is still important. With so many buildings and businesses closing for extended periods in the past year and a half, it is crucial that building owners and facility managers understand the increased risk for an outbreak due to the water and air conditioning systems sitting with potentially no usage for weeks or months. As businesses reopen and employees come back to the office, maintenance personnel should flush water lines and systems before use. Managers of older buildings or businesses serving clients at a higher risk of getting Legionnaires’ disease should have their systems tested after flushing and verify that standard operating conditions will kill Legionella and not allow growth. While Legionella can never be eliminated, with appropriate monitoring, prevention, and education, serious outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease could be a thing of the past.